Read the latest in finance and investment news in our Investment and Economic Snapshot for January 2024.

Read the latest in finance and investment news in our Investment and Economic Snapshot for January 2024.

In this paper we aim to explain our expectations for inflation, our views on when central banks will adjust rates and the implications of these on equity and bond markets.

What is inflation and when can it be a problem?

Inflation refers to the sustained increase in the price of goods and services. Broadly, it is quantified by measuring the change in prices for a basket of goods and services – which is known as the all-familiar Consumer Price Index (“CPI”).

Inflation occurs when economic activity is increasing and there is a mismatch in demand and supply, thereby resulting in price increases. This can be driven from the supply side (known as “cost-push”) or from the demand side (known as “demand-pull”). Left unchecked, inflation can be detrimental as it erodes the purchasing power of money and diminishes the real returns of invested assets, resulting in a host of negative flow-on impacts to both consumers and governments alike.

However, inflation is not inherently always an issue. When inflation is increasing at reasonable levels, most central bank’s target an annual inflation range between 2-3% p.a, it signals a growing economy which is beneficial for all market participants. It is only when inflation rises too far above these “healthy” levels that the erosion of the consumer’s purchasing power (and its corresponding effects) outweighs the benefits flowing from the economic expansion.

(a) Short-term inflation expectations

Headline inflation indicators (like CPI) will likely spike over the next few releases, as the base effects of the abnormally low inflation data from a year ago falls out of annual calculations. Keep in in mind that annual CPI is the aggregate of monthly inflation over the previous 12 months, so when especially low numbers drop out and are replaced by stronger monthly numbers, then annual inflation will rise – this is what we mean by ‘base effects. Another factor likely to add to inflationary pressures are supply constraints, an example of this issue can be found in the global production and supply of semi-conductors which are a key component for products that contain computer chips. As a result of production shutdowns caused by COVID-19, supply was dramatically reduced and is only now slowly returning to normal. The impacts of this have been felt far and wide, with everything from cars to farm machinery seeing production shortages. We expect these issues to be resolved over coming months and therefore they should only have a transitory impact on prices. In turn, these issues create uncertainty in bond markets as the prospect of rising prices (and by extension, inflation) increases the likelihood of central banks raising interest rates to prevent the economy from overheating. However, we expect the current inflationary climate to be temporary and unlikely to result in inflation remaining above central bank targets in the immediate future.

A key macroeconomic indicator for investors to watch is the Output Gap (refer to Appendix 1) which represents the capacity utilisation of an economy. When this measure is negative, it indicates spare capacity and inflation is unlikely to be an imminent problem. Currently, the output gap in the US is -1.59% and this is mirrored in most developed nations, including Australia, as they continue to feel the effects of COVID-19. As a result, we believe it will be some time before the Output Gap narrows and causes inflation to remain above central bank’s targets.

When will inflation become an issue?

(a) US

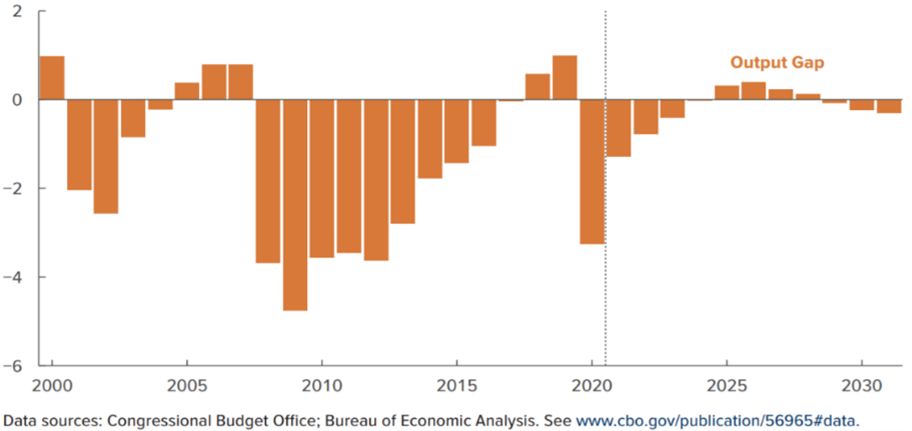

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) forecasts the output gap for the US, which the US Federal Reserve (“FED”) uses as an input to monetary policy decisions. The CBO’s most recent projection (Figure 1 below) suggests they do not see an imminent threat to markets from excessive inflation.

Figure 1 – US Output Gap

Whilst the CBO does not see inflation being an issue for several years it is important to highlight several variables that could significantly impact this forecast.

The first variable that could impact how quickly the output gap closes is the size and structure of US fiscal policy implemented as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. One key policy was the infrastructure stimulus package handed down by President Biden (Democratic party) in March 2021. Given the package has not yet been signed into law, the CBO did not include this in their most recent forecast. It is expected this package will accelerate actual GDP faster than the CBO’s forecast. The increase in government bond yields over the last 12 months would suggest the market supports these views.

Another key variable that could result in inflation becoming an issue faster than the current estimate is the speed at which the US labour market recovers. Currently the unemployment rate in the US is still above pre-COVID-19 levels. However, given the recent upgrades in the outlook for economic growth and the reopening of service-oriented industries that suffered during the pandemic, we expect unemployment to gradually return to more normal levels but anticipate periods of volatility along the way.

Furthermore, although we have recently seen tightening in the labour market as demand outstrips supply, we believe this will pass as government unemployment benefits roll off and remaining COVID-19 restrictions are lifted. As a result, we are likely to see more people re-entering the work force which in turn will drive up the participation rate and offset the current labour shortage. We expect overall levels of unemployment to improve but do not anticipate that the labour market will tighten to a level where we will see significant wage inflation over the short to medium term.

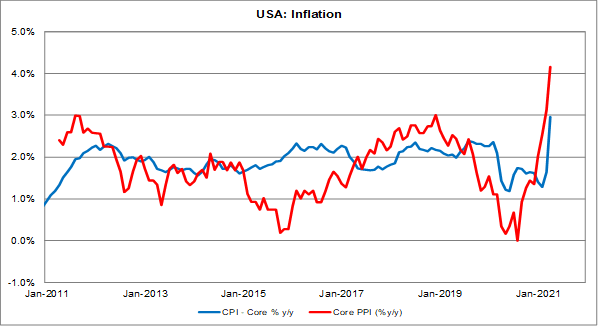

Recently there has also been some focus on spikes in the cost of production. While there is evidence that there has been a surge in the cost of production, it is our view, and that of central banks around the world, that the supply constraints causing these price rises will also be temporary. Once economies reopen and return to full capacity these supply constraints will subside. A key indicator used to measure the cost of production is the Producer Price Index (“PPI”) which tracks the change in prices received by producers. It is worth noting that the rising cost of production (PPI) does not automatically translate into increased inflation (Core CPI), as we can see from the chart (Figure 2 below).

Figure 2 – Inflation vs PPI (Annual)

Taking these facts into consideration, we are adopting a ‘middle ground’ view. Whilst we do not fully agree with the CBO and FED’s view that inflation will remain subdued for several years, we are also not convinced it is an immediate issue. As such, we anticipate inflation in the US is likely to become an issue somewhere around mid-2022.

(b) Australia

The same underlying outlook applies to the Australian economy. Similar to the US, we do not believe that inflation is an imminent issue and that the trajectory of inflation in Australia is likely to be more modest than the US.

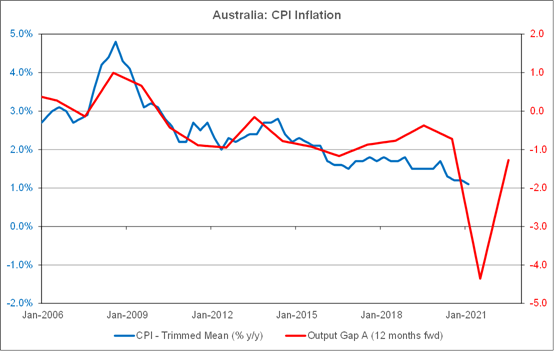

The current output gap in Australia (see Figure 3) suggests inflation will be a little over 1% at the end of 2021 and will steadily rise to 1.5% through 2022 and 1.75% by mid-2023. Based on this forecast, Australia will still be sitting below the RBA’s CPI target of 2% at the end of 2023.

Figure 3 – CPI vs Output Gap

This forecast aligns with the current market consensus which suggests the output gap in Australia will reduce at a slower rate than the US output gap. Unlike the US, the Australian government has implemented more moderate fiscal spending packages. However, given the cyclical nature of the Australian economy, as growth momentum builds globally, we anticipate the output gap will close and therefore likely accelerate inflation faster than current expectations.

When will central banks start to increase interest rates?

Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, a number of central banks modified their framework for determining when they adjust interest rates. In the US for example, previously the FED had utilised hundreds of internal models and experts to forecast inflation and would determine changes to the cash rate based on this information. Recently there has been a shift in methodology which resulted in two major modifications to the process. The first is that instead of relying solely on inflation forecasts they now use a combination of forecasts and actual inflation data. The second is that instead of automatically reacting when inflation moves significantly away from target, they are now willing to accept periods of higher or lower inflation so long as the average level of inflation remains at the bank’s target level of 2% over the medium term. The implications of these changes suggest that there would need to be a prolonged period of realised inflation/deflation above or below the 2% target inflation level to necessitate a response from the FED. These changes are designed to remove the likelihood of data spikes distorting forecasts which could result in an unnecessary change to the cash rate, much like what happened after the Global Financial Crisis (“GFC”).

Current expectations by the Australian and US central banks have indicated that they do not intend to tighten monetary policy (i.e., increase rates) until 2023/24. Managing the cash rate is a balancing act – while the banks want to provide an accommodative environment to allow the economy to recover, they do not want to let inflation get out of hand. But given the recent changes in policy as well as the lessons learnt during the GFC when cash rates were raised too quickly, it seems likely that the central banks will take a more conservative approach and will allow inflation to run more than they previously would have tolerated. That said, whilst we do not expect cash rates to change in the next 12 months, we do anticipate they will increase sooner than central banks’ current time frames.

Our analysis suggests that inflation is unlikely to become an issue in the US until the second half of 2022, and mid-2023 in Australia. As such, we expect the FED, and the RBA will begin to raise rates around the same time.

What will rising rates mean for equities?

The impact of rising interest rates and inflation more generally will affect equity markets differently depending on the country, sector, or style of the underlying stocks. A key factor to watch will be the current valuation of the asset relative to its value historically. It is likely that assets that have significantly outperformed and sit well above their historic valuations will be most affected by a rise in interest rates.

(a) Equity valuations

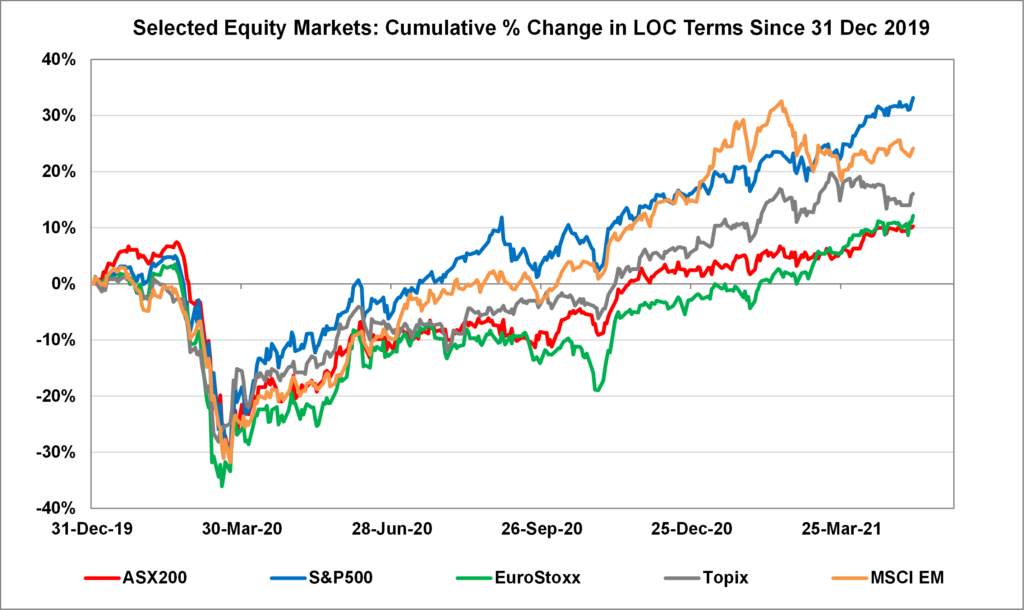

The majority of global equity markets experienced a strong rebound in returns following the COVID-19 drawdown in February and March 2020, but some markets have recovered faster than others (see Figure 4 below). In some instances, valuations have surpassed their pre-COVID-19 levels and made new historic highs.

Figure 4 – Cumulative % Change in Equity Markets

In the US, for example, the S&P500’s current Price to Earnings ratio is 23.5x, 17.5% above its pre-COVID-19 levels and 38% above its long-term average. On the other hand, several other developed markets like Australia, Europe, and Japan have not recovered as much and on a relative valuation basis look more attractive for investors.

Whilst we expect rising rates to be a headwind for equity markets (as the prospect of rising rates increases the cost of capital and reduces future earnings), we anticipate countries with elevated valuations, like the US, will be impacted more than markets that have seen more modest recoveries.

Similarly, at the sector level, some sectors have recovered faster than others following the COVID-19 drawdowns in early 2020. Sectors like Information Technology, Healthcare, and Consumer Discretionary have benefited from COVID-19 restrictions, recovering rapidly, and reaching new highs after their initial drawdown. However, this is not the case for all sectors, with Property, Infrastructure, and Resources lagging the market through 2020. When central banks inevitably do increase interest rates, the market’s reaction will differ depending on the relative valuation levels of the sector. Our view is that those sectors that do not have excessive valuations will endure the effect of rising rates considerably better than those that have historically high valuations.

What is also evident is that the sectors that underperformed during the COVID-19 recovery are the segments of the market that will likely benefit when economic growth is stronger (pro-cyclical). Along with having more modest valuations, we believe these sectors will benefit from the more positive economic growth outlook, further insulating their future returns from the impact of rising interest rates.

(b) Growth or Value Investing?

There has been much discussion around the relative performance of growth vs value, with growth stocks outperforming value stocks over the past 10 years. It is not unusual for one style to outperform another however, these deviations normally mean revert over the long term.

Growth stock performance is typically negatively correlated to interest rates which has been one of the major drivers of the outperformance of the growth style over value over recent years. Due to the way growth-style companies’ earnings and valuations are calculated, these assets have an inverse relationship with interest rates, so when central banks eventually increase interest rates, it will drag down the future earnings and valuations of these stocks.

The disparity in performance of growth and value stocks only increased during the COVID-19 recovery with growth stocks benefiting from lockdowns and a subdued economic outlook, which intensified expectations that interest rates would remain low and accommodative. This supportive environment resulted in growth assets quickly returning to extremely elevated valuations and, in some cases, passing historic highs. This only increases growth stocks sensitivity to a rise in future interest rates.

Although we have seen signals that value stocks are starting to benefit from economies reopening and the positive economic outlook, on a relative basis, the valuations for these stocks are still well behind growth stocks. As such, we do not believe the impact of rising interest rates will be as significant for these stocks. In addition, the value universe is comprised of mainly pro-cyclical companies that benefit from the global growth narrative.

In summary, assets that are more closely tied to the global recovery (value stocks) will be less sensitive to an interest rate rise. Whilst we have seen the early signs of a rotation back to value/cyclical style stocks, given the scale of the underperformance of these stocks over the last 10 years, we believe there is still some way to go in this trade.

What will rising inflation and interest rates mean for fixed income markets?

Rising rates due to higher inflation are likely to be a headwind for fixed income markets given the sensitivity of fixed income assets to changes in interest rates. Most bonds pay a fixed coupon that becomes more attractive if interest rates fall. The calculation of the annual coupon as a percentage of the bond price is known as “yield”.

As interest rates rise, the price of the fixed-coupon bond falls (inverse relationship) as newer bonds issued at the prevailing higher interest rate are more attractive to investors. The price of the bond falls to compensate the investor for the opportunity cost of not investing in these newly issued bonds paying higher coupons. As a result, we anticipate fixed-income assets may struggle in an environment when inflation and interest rates are increasing.

However, much like equities, the magnitude of these impacts will differ from bond to bond. Broadly, bonds’ sensitivity to interest rates is measured by a metric known as modified duration (“duration”) – the longer the duration of a bond, the higher the sensitivity to rising interest rates. A number of factors will impact the duration of a bond. The most significant factors are the length of time to maturity and the coupon rate. The greater the length of time until maturity and the lower the coupon, the longer the duration. In a market where inflation is rising and central banks are increasing interest rates, fixed coupon paying bonds that have shorter duration will be less impacted than those with a longer duration.

Along with duration, another factor that will determine how fixed-income assets perform is its underlying category – for most bonds this is whether it is a government or corporate issued bond. The key difference between these two classes of bonds is in their credit quality. In general, corporate bonds will offer higher yields to compensate the investor for taking on additional credit risk. In contrast, government bonds – for the most part – are used as a proxy for risk-free assets as governments will always be able to print money to service existing debt obligations. Credit quality is affected by many things, including the state of the economy, a company’s performance, and its debt burden.

In an environment where economic growth is strong, it is likely that most companies’ credit quality will improve. However there comes a point with any asset, where future expectations are already priced into the asset value, which can then result in a period of stagnate returns. We believe this point has been reached with corporate bonds, as improving growth expectations have already seen strong performance from these assets over the previous 12 months.

The Output Gap

The Output Gap is the most widely accepted leading indicator on the trajectory of inflation and is a major input into the central banks’ decision-making process. The Output Gap is defined as the difference between actual and potential GDP. The simplest way to think of potential GDP is the output of an economy if it was operating at full capacity, while actual GDP is the level of output the economy truly produced.

In a climate where potential GDP is greater than actual GDP there is excess capacity in the economy and as a result there is no supply or demand pressure pushing or pulling prices up. However, when actual GDP is greater than potential GDP this suggests that the economy is operating above its capacity which in turn creates constraints particularly among businesses as they compete for the same resources and labour. This competition puts upward pressure on wages and other associated inputs, resulting in prices rising (inflation). Typically, we would expect to see 12-18 months of actual GDP outstripping potential GDP before these capacity constraints start impacting prices.