Summary

The Trump administration signalled a shift toward diplomacy, engaging in multiple bilateral trade negotiations and securing a temporary but significant reduction in tariffs with China. This move helped restore investor confidence, with equity markets rebounding from April losses. US markets are increasingly pricing in the prospect of ongoing dialogue and a reduced economic impact from trade tensions.

Despite these developments, the US maintained a broadly protectionist stance, notably raising tariffs on steel and aluminium. However, a recent unfavourable court ruling has raised legal questions around President Trump’s ‘Liberation Day’ reciprocal tariffs.

On the monetary policy front, the US Federal Reserve opted to hold interest rates steady, citing elevated uncertainty. In contrast, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) took a more proactive stance, cutting the official cash rate to 3.85% in an effort to support domestic growth.

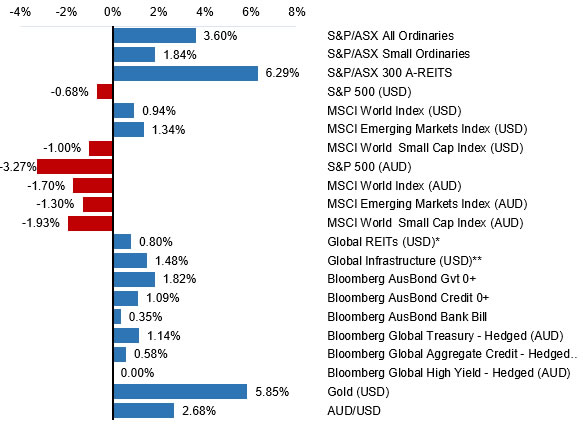

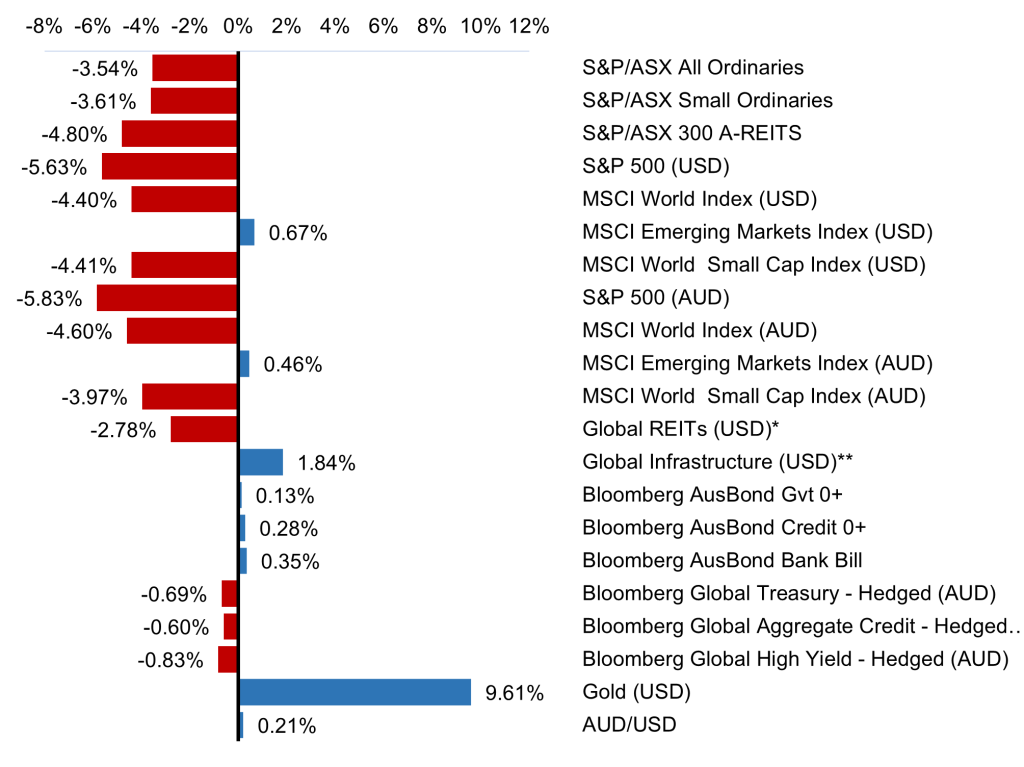

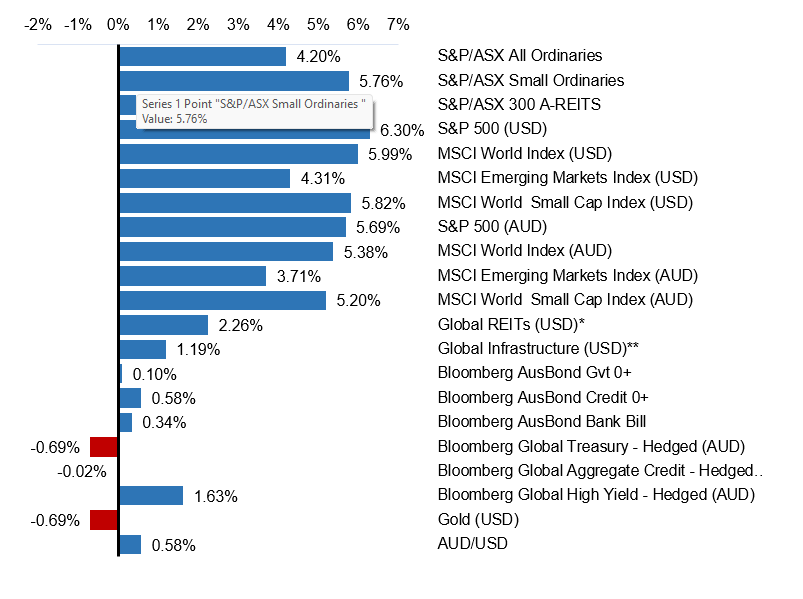

Selected market returns (%), May 2025

Sources: *FTSE EPRA/NAREIT DEVELOPED, **FTSE Global Core Infrastructure 50/50 Index

Key market and economic developments in May 2025

Financial markets

Global equity markets quickly recovered losses from April, with the MSCI World (USD) rising a sizable 6.0% during the month, led by the US market, with the S&P 500 rising 6.3%. The US market total return is now positive for the 2025 calendar year, although it is yet to reach its previous high on February 19.

Australian equities

The ASX 200 posted a strong gain of 4.2% in May, pushing calendar year returns into positive territory and bringing the index just shy of its all-time high set in February 2025. The Financials sector remained the primary driver of performance, returning 5.1% for the month, led by index heavyweight Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA), which rose 5.6%. Over the past 12 months, CBA has delivered an impressive 52% return, making it by far the largest contributor to Australian equity market gains.

Information Technology was the standout performer in percentage terms, surging 19.8% as global growth and tech stocks rallied sharply. Energy also delivered solid gains, rising 8.6% despite relatively flat oil prices. Meanwhile, the Resources sector continued to underperform on a relative basis, managing a modest 1.8% increase for the month.

Global equities

There was widespread strength in global equity markets, as a relief rally was broadly felt across developed and emerging markets. The US market was driven higher by large cap technology, with a 9.2% rise in the Nasdaq 100 (USD) index. The broader S&P 500 (USD) was up 6.3%, while the Russell 2000 (USD) small cap index was up 5.8%. Markets across key trading partners were also very strong, with the Euro Stoxx 50 (EUR) index, Japanese Nikkei 225 (JPY) and the Hang Seng (HKD) rising 6.0%, 5.3% and 6.6% respectively.

The US earnings season through May was again relatively robust, with 78% of companies exceeding Earnings per Share (EPS) estimates, in line with the 5-year average[1]. Companies reported annual earnings growth of 12.9%, which supported the market. There were concerns that companies would downgrade or withdraw their guidance for profits in upcoming quarters, which typically hurts investor confidence. However, from S&P 500 only 8 companies withdrew guidance and 37 downgraded, with 64 increasing and 139 maintaining guidance.

Commodities

Commodity markets delivered mixed performance in May. Gold posted a modest decline of -0.7%, reflecting a moderation in tariff-related concerns and a more tempered risk environment.

Crude oil prices continued to weaken amid a shift in OPEC+ dynamics. Led by Saudi Arabia, key producers ramped up output in an effort to reclaim market share and exert pressure on member nations exceeding production quotas. With global markets already well-supplied and demand outlooks uncertain, Brent Crude fell to $61 per barrel, weighed down by oversupply concerns and broader economic uncertainty.

Bond markets

US bond markets saw yields increasing through May, leading to lower prices, especially for longer dated bonds. The US House of Representatives narrowly passed the ‘One Big Beautiful Bill’ budget, which is estimated to add $2.4 trillion to the US deficit over a decade,[2] leading to further concerns around fiscal sustainability. This was compounded by a poor outcome from an auction of new 20-Year US Treasury Bonds and a sovereign credit downgrade from Moody’s, leading to pressure on bond prices. Long dated 20 and 30-year bonds finished the month just under the psychological 5% level, while the 10-year rose from 4.16% to 4.39%.

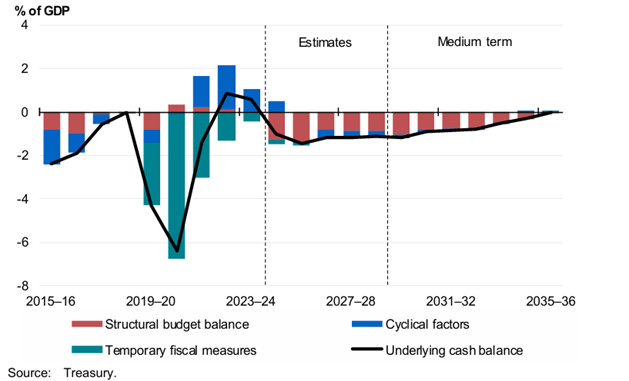

Domestically, Australian bonds also drifted higher but to a lesser extent, reflecting a better fiscal situation in Australia and market expectations of further rate cuts from the RBA.

Economic developments

RBA cuts interest rates

As anticipated, the RBA reduced the cash rate from 4.1% to 3.85% in May. The decision was largely driven by a more favourable inflation outlook, as we noted in April. The RBA highlighted that year-on-year trimmed mean inflation (to the end of March) eased to 2.9%, with headline CPI at 2.4%, and both measures are expected to remain broadly stable in the near term.

The RBA described domestic economic conditions as mixed. The labour market remains resilient, with the unemployment rate holding steady at 4.1%. However, consumer spending and sentiment have softened more than expected. While the RBA reiterated its data-dependent approach to future policy moves, market participants are now pricing in two to three additional rate cuts over the course of 2025.

US Court of International Trade throws tariff into doubt

In a surprise ruling in late May, the US Court of International Trade unanimously ruled that the Trump administration’s sweeping ‘Liberation Day’ tariffs, introduced under the 1977 International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), were unlawful. President Trump had cited the US trade deficit as an “ongoing emergency” to justify the tariffs, but in a detailed 50-page judgment, the court found that the IEEPA does not grant the President the authority to impose tariffs in this manner. The ruling casts serious doubt over the legal foundation of the policy. The administration has since appealed, with expectations that the case could eventually reach the Supreme Court.

This legal setback exposes a vulnerability in President Trump’s trade strategy, particularly given the lack of precedent and the unanimous nature of the ruling. It also raises questions about the administration’s ability to impose tariffs unilaterally, as seen earlier in the year. The uncertainty may prompt trade partners to adopt a more cautious, wait-and-see approach to negotiations, potentially delaying progress on new agreements.

While the ruling specifically targets the IEEPA-based tariffs, other trade restrictions, such as those on steel, aluminium, and autos, remain in place under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act, which allows for tariffs on national security grounds. These measures, although also facing legal challenges, may serve as alternative tools for the administration to advance its protectionist agenda.

Outlook

Uncertainty with respect to US government policy, the economy and the market remains elevated. However, a closer look at economic and market fundamentals reveals several areas of resilience that should not be overlooked. While zero-sum trade tensions act as a drag on global growth, they may be partially offset by several constructive developments, such as continued advances in AI driving productivity, fiscal reform and rate cuts in Europe, and ongoing stimulus and structural reform efforts in China.

Although the range of potential outcomes is broad, our base case remains that the global economy and markets will likely experience bouts of volatility but continue to move forward. In this environment, we see strong value in diversification as a key risk management tool. We see significant benefit to investors in diversification to manage risk and believe that remaining active and alert to risks and opportunities is crucial.

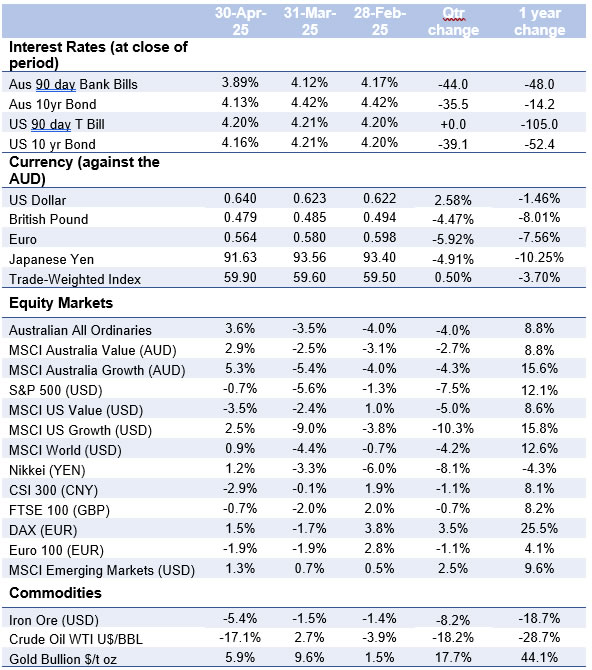

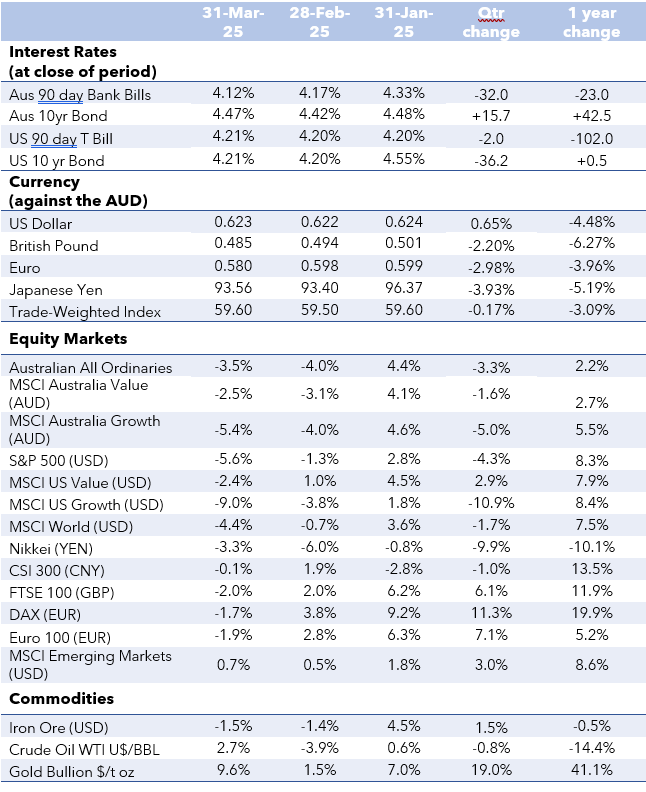

Major market indicators

| 31-May-25 | 30-Apr-25 | 31-Mar-25 | Qtr change | 1 year change | |

| Interest Rates (at close of period) | |||||

| Aus 90 day Bank Bills | 3.73% | 4.02% | 4.12% | -44.0 | -63.0 |

| Aus 10yr Bond | 4.28% | 4.13% | 4.42% | -14.2 | -4.4 |

| US 90 day T Bill | 4.25% | 4.20% | 4.21% | +5.0 | -100.0 |

| US 10 yr Bond | 4.39% | 4.16% | 4.21% | +19.0 | -10.0 |

| Currency (against the AUD) | |||||

| US Dollar | 0.644 | 0.640 | 0.623 | 3.49% | -3.23% |

| British Pound | 0.478 | 0.479 | 0.485 | -3.30% | -8.49% |

| Euro | 0.567 | 0.564 | 0.580 | -5.22% | -7.56% |

| Japanese Yen | 92.70 | 91.63 | 93.56 | -0.75% | -11.40% |

| Trade-Weighted Index | 59.60 | 59.90 | 59.60 | 0.17% | -5.55% |

| Equity Markets | |||||

| Australian All Ordinaries | 4.2% | 3.6% | -3.5% | 4.1% | 12.4% |

| MSCI Australia Value (AUD) | 3.0% | 2.9% | -2.5% | 3.3% | 10.9% |

| MSCI Australia Growth (AUD) | 4.9% | 5.3% | -5.4% | 4.5% | 19.7% |

| S&P 500 (USD) | 6.3% | -0.7% | -5.6% | -0.4% | 13.5% |

| MSCI US Value (USD) | 2.7% | -3.5% | -2.4% | -3.4% | 8.4% |

| MSCI US Growth (USD) | 10.0% | 2.5% | -9.0% | 2.6% | 19.5% |

| MSCI World (USD) | 6.0% | 0.9% | -4.4% | 2.3% | 14.2% |

| Nikkei (YEN) | 5.3% | 1.2% | -3.3% | 3.0% | 0.6% |

| CSI 300 (CNY) | 2.0% | -2.9% | -0.1% | -1.0% | 10.8% |

| FTSE 100 (GBP) | 3.8% | -0.7% | -2.0% | 1.0% | 10.1% |

| DAX (EUR) | 6.7% | 1.5% | -1.7% | 6.4% | 29.7% |

| Euro 100 (EUR) | 5.8% | -1.9% | -1.9% | 1.8% | 6.7% |

| MSCI Emerging Markets (USD) | 4.3% | 1.3% | 0.7% | 6.4% | 13.6% |

| Commodities | |||||

| Iron Ore (USD) | -1.6% | -5.4% | -1.5% | -8.3% | -19.3% |

| Crude Oil WTI U$/BBL | 3.5% | -17.1% | 2.7% | -11.9% | -20.9% |

| Gold Bullion $/t oz | -0.7% | 5.9% | 9.6% | 15.2% | 41.0% |

Sources: Quilla, Refinitiv Datastream

[1] According to Factset

[2] According to Yale Budget Lab